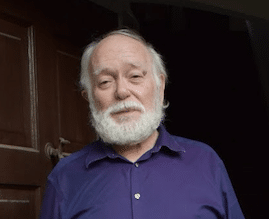

Carter Curtis Revard

Carter Curtis Revard died on the morning of January 3, 2022 at the age of 90 at his home in University City in St. Louis County, Missouri.

He was born in Pawhuska, Oklahoma in 1931, along with his twin sister, Maxine, to Thelma Louise Camp and McGuire N. Revard. He was raised in the Buck Creek Valley on the Osage reservation by his mother Thelma, who married his stepfather Addison Jump. Together Addison and Thelma brought along and cared for him and his six siblings—Antwine Pryor (his elder), Maxine Revard, Ireta “Josie” Jump, Louis “Jim” Jump, Josephine Jump, and Addison Jump Jr. As he writes in his autobiography Winning the Dustbowl, he grew up part of “a mixed-blood family of Indian and Irish and Scotch-Irish folks,” which includes more cousins and aunts and uncles and grandparents and nicknames than can easily be included here. His mother’s brother, Woodrow “Woody” Camp, and his beloved aunt Jewell McDonald merit naming, though, as do their children, his Ponca cousins: Darlena, Carter, Dwain (“Bucky”), Craig, and Katherine (“Casey”).

After attending the one-room Buck Creek School for the first eight grades, he went on to be graduated from Bartlesville College High School, then to attend Tulsa University on scholarship, having placed third in a radio quiz scholarship competition. He was graduated from Tulsa University (1952), then earned a Rhodes Scholarship, which allowed him to study at and receive a degree from Merton College, Oxford in 1954. In 1952, on receiving his Rhodes Scholarship, he was given his Osage name, Nompehwathe, by his Osage grandmother, Josephine Jump. In 1956 while working on his Ph.D. in English at Yale University, he met and married his fellow English scholar, Dr. Stella Hill Purce Revard. He completed his Ph.D. in 1959 and subsequently taught at Amherst College in Massachusetts. Beginning in 1961, he taught at Washington University in St. Louis, where he remained, retiring officially in 1996 but persisting (for all good professors do) as emeritus to shepherd many young scholars onward.

In addition to teaching at Washington University and as a visiting professor at the Tulsa University and the University of Oklahoma, Revard published scholarly and creative work of great variety. His research into the Harley manuscript and his general work on medieval literature was an early and continuing focus for him. His expertise in linguistics and lexicology led him briefly to collaborate on the government efforts to put the English lexicon into computers in 1967. His devotion to Native American culture led him to be an enduring voice for inclusivity and multiculturalism in the classroom, in countless works of criticism, and in his essays and poetry. Indeed, a distinctive voice resonates in all his poetry, beginning with the chapbook My Right Hand Don’t Leave Me No More (1970), then Ponca War Dancers (1980), and continuing with Cowboys and Indians, Christmas Shopping (1992), An Eagle Nation (1993), How the Songs Come Down: New And Selected Poems (2005), and concluding with From the Extinct Volcano, A Bird of Paradise (2014). These books of poetry were paired with two works of autobiography: Family Matters, Tribal Affairs (1998) and Winning the Dustbowl (2001) that tell his story fully. In all these works, as he says in his dedication to How the Songs Come Down, his principal and humble concern lay with “the small birds only/ whose life continues on the gourd/ whose life continues in our dance…” He listened and looked first for those small birds and sought to praise their power of flight as what sustains us all, first and last.

Carter Revard was preceded in death by his wife, Stella, in 2014. He is survived by his brothers Louis “Jim” Jump and Addison Jump Jr., his sister Josephine, and his children, Stephen Revard, Geoffrey Revard, Vanessa Roman, and Lawrence Revard.

Due to the ongoing pandemic, memorial services will be held in the summer of 2022 when conditions allow.

Carter Revard

Carter Revard directed my PhD dissertation at Washington University in St. Louis between 1986 and 1989. In 2006, elements of that dissertation appeared in my book on the medieval poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Those twenty years are reflected in my dedication of that book to him. For this appreciation now, I have just re-read what I wrote then in my acknowledgments, and each word continues to sound exactly right to me:

I have looked forward to expressing formally my debts to Carter Revard as the medievalist who ushered me into my profession. I am grateful: I cannot conceive a more sustained interest and helpfulness than Carter’s over the long period of this book’s writing from its remote origins in the dissertation I did with him. But it is really admiration that I have most wanted to put into words, for that quality that led an established scholar to handle a real neophyte so collegially.

Carter made available every last resource of his own extraordinary knowledge, volunteered whatever he thought might help, replied instantly and abundantly to whatever questions, read and responded to swathes of manuscript, placed a constant faith in the project, and never lost touch. This attentiveness, coming from a surpassing expert on medieval English scribal hands, flattered and fortified someone given to looser gestures. It is Carter’s whole-hearted generosity as a scholar to which I wish to pay tribute in dedicating this book.

I knew the same Carter in the years since 2006, through the same kind of correspondence, and through our periodic meetings at conferences. When we met, Stella was often there: what a union that seemed to be. Meanwhile, I read and was amazed by his poetry (How the Songs Come Down, From the Extinct Volcano), where I felt in the company of a man in love, and in love with not only this earth, but the cosmos. Now I think about it, in love with the intersection between words in their capacity for precision and for play, and the earth/cosmos; love being a fascination with and an absorption in. So he continued to be a source of reassurance for me, someone whose way of conducting his vocations spoke to my own occasional doubts. You could get lost in the minutiae of times long ago gone, questions that for many would be long moot, and be someone ethically rooted in the depths of the political present; you could be scholar and creative spirit.

And you could be a good man, if one presumes to even be able to make such statements. May I here say that there was something apart, even otherworldly, about Carter. We communicated across a distance that appeared necessary, the ground condition of the communication. I cannot imagine a person who across such a distance could come across as gentler, warmer, more present in and truer to his word.

Everything together leaves me somewhat in awe of a life I can barely scratch.

Francis Ingledew

Professor Emeritus of English Literature

Fairleigh Dickinson University, NJ

Good-bye, Carter, my friend. Your sagacity, goodness, word-fun, warmth, and love of discovery in old books have lifted me tremendously for decades. When I was a younger scholar, you were a beacon of inspiration. Whenever you shared your wisdom with me, it was a deep honor. Thank you, and good-bye with love and affection.

Carter, the first book of poems I read by you was Ponca War Dancers, and I much enjoyed it! When I began teaching at Western Connecticut State University in the mid-eighties, Steven Neuwirth mentioned having been a colleague when he was at Washington U. By the time we met at Returning the Gift in 1992, I had learned you were a scholar of medieval literature and that your sense of humor, poker-faced with an eye twinkle, I had observed of scholars and teachers in that field since my college days, a look as if you’d swallowed any of The Parliament of Fowls within reach! Thanks for briefly visiting my Intro to American Studies class at UMass when you stopped in Amherst a while back. And thanks for being You.

Remembering Carter Revard

Whether you have 8 or 12 or 16 or even 20 years of formal education, there are just a very few teachers, if any, who stand in memory, having reached out to help us on our way. I was privileged at Washington University to have had more than my share of such mentors and later too at Indiana University, due to good advice from Carter Revard, and others too, so that I stumbled into a legacy of generosity among those who had studied with or who had taught one another along the way.

Carter was that first open-handed teacher, the one who pulled me aside in the spring of my sophomore year in a survey course on Middle English literature to begin a conversation that ran for forty years. “You’ve read the Bestiary,” he once said that spring; “now read Richard Wilbur’s animal poems—read `A Barred Owl.’” He matched the generosity of his learning with that of his correspondence. I look back now over letters and messages filled with family updates, poems, and questions, remembering meetings in the great jumble of his office, sitting over toast and coffee in the kitchen, walking and talking in St. Louis or Kalamazoo or London. (I first gained entrance to the old Reading Room at the British Library when Carter vouched for me in person). One of the great privileges of my academic life was to return to Washington University to teach for a year and share time with Stella and Carter. On Friday afternoons he’d join the circle of a Middle English reading group and we would listen as he read, then work together over words and phrases that slipped past easy translation. I read his words now and hear Carter’s voice, one of the most remarkable instruments I have ever been privileged to learn from and to enjoy. We wrote too as each of our beloved spouses fell into ill health, and we lost them. The depth of Carter’s love for Stella was plain to me at age twenty, when I read a poem he’d written about her, and ever after. He lived no part of his life in a shallow way. He was a full-grown man.

I remember those first books in medieval studies he recommended, always encouraging me to keep learning; it was at his prompt that I came to read as well as Joy Harjo, Linda Hogan, Simon Ortiz, James Welch, and many others. I’ve many times read over his poems and memoirs, sharing them with friends, so very glad to see the respect for his work, keen as the cry of red-tailed hawk, and for his scholarship, his patient pacing after scribal traces, acknowledged for its sharp-eyed brilliance. As the old poet might say, using a word that was Carter’s through and through: he wrixled words so well.

A few years ago, not long before I shared some time with Carter in Toronto, where his wonderful voice would ring out to open the Biennial Congress of the New Chaucer Society, I bought an old motorcycle in Coffeyville, Kansas, and rode south to Oklahoma, to Bartlesville and the Caney River, then west along highway 60 and down into Pawhuska. I wanted to look over a little of Carter’s country, listen a while in the places that shaped him: “See friends, it’s not a flyover here.” I miss his voice. I hold his poems, his books, his words close by, and will keep listening to learn from him.