Helen (Loila von Lerche) Klingenberg

Helen

July 12, 1928 – September 22, 2020

As the first day of autumn, September 22, 2020, came to a close, Helen (Loila von Lerche) Klingenberg opened her sky blue eyes after days at death’s door and gave one last, long look at the world. This is her tale.

Helen’s ninety-two years read like a Tolstoy novel, with Mother Russia and world wars setting the stage of her historically rich life. Born in 1928 Berlin, Germany, to parents of Russian aristocracy who had escaped St. Petersburg during the Bolshevik Revolution, both Russian and German were her native tongues. Bilingualism could be a saving grace for Germans who found themselves among Soviet troops during the close of the Second World War and the Era of Partition. However, for Helen, who often could not resist speaking her own mind, it was a double-edged sword.

As the story goes, at the age of 19, she was traveling outside Berlin to visit her mother who had just given birth to Helen’s new baby sister. Helen, upon overhearing disparaging remarks made by Soviet soldiers on her train, let out an angry retort, which landed her in a Soviet detention center. Fortuitously, her father, who had found work transporting oil for the Russians, happened to be walking through that very facility at the moment she was being interrogated, and he was able to negotiate her release. If not for that serendipitous intersection, her where-abouts may never have been known. Luck like that seemed to travel with Helen throughout her life and made her oblivious to how harrowingly close to danger she often stepped.

Perhaps a guardian angel found Helen during the years she attended mass at the Russian Orthodox Church with her beloved and devout “Mama.” To her mother’s disappointment, however, Helen did not embrace this heritage, but the hours of Latin she heard there must have seeped into her soul. She read Latin easily, and became fluent in English as well. She also picked up French, in a passing fashion. Although every German child was required to learn languages in school, Helen seemed especially adept, picking them up like freshly fallen apples from a ripe orchard lawn. When she immigrated to the United States, she put this skill to use, translating letters for friends and work colleagues with ease and accuracy.

Helen loved to read — anything and everything. Tucked in her purse, she always carried a paperback book to fill the empty minutes while waiting for appointments and made regular trips to Goodwill’s dollar bookcart to resupply her habit. Long before she came to America, German author Karl May’s stories of the Old West captured her childhood imagination. She escaped into her books regularly, ignoring the reality of her basement bomb shelter, only abandoning the asylum of the bound-pages when it meant helping a furry friend . On one occasion she thwarted the adults who urged her toward the crowded room, refusing to go underground unless they broke the rules and allowed the neighbor’s big dog to join her.

Over the years, perhaps as a coping mechanism, she developed a wry humor. It became a defining part of her personality, which she exercised daily as she observed the neighborhood gossip. To Helen, this was the mysterious space between truth and fiction, which was much more interesting than the dryly reported news. The more extreme the better. She couldn’t resist the oddity of a salacious tabloid headline about Bigfoot or aliens.

In her sixties, when the Internet came along, Helen was an early adopter. Not just for the endless access to the world’s news; to her it was “the greatest thing that ever happened.” This wasn’t surprising to hear from someone whose family had scattered like breadcrumbs after the war. Throughout her life she could claim family across the globe — in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia and North America — and her computer became her favorite way to stay connected.

Childhood before the war held memories of picking up amber from the beaches of the Baltic (with hopes of finding a piece with a prehistoric mosquito in it) and foraging for mushrooms in the forests. Later as a teen living through the Allies’ bombing of her city, Helen must have seen indescribable destruction, but she left those memories buried in the rubble. Mostly, she dwelled in the land of rainbows and unicorns, never losing her childlike enthusiasm and sense of wonder. The dark side of that past was only made evident through her Orewelian proclamation, “Four-footers are better than two-footers,” which explained the endless parade of creatures that took up residence within the Klingenberg household over the years. This philosophy characterized her outlook on life and hinted at a war-born cynicism to those who knew her history. To those who didn’t, her sass and go-against-the-grain personality were thought of as eccentric, even strange. Helen delighted in this.

She was quirky, in the best way, and laughed easily. Unencumbered by social convention, Helen was uncharacteristically German, known for her every-day defiance of the “stuuu-pid” rules. Neighbors, friends and family alike can recount many instances of her do-and-say-as-I-like attitude. According to Helen’s children, when she picked them up from grade school, she always ignored the “wrong way” sign posted in the circle drive. All the other kids stared at them with amusement, gawking at the spectacle their mother created. A line of buses caravanned into the street, unable to enter the area. Their principal begged, “Could you please ask your mother not to do that?” It was a losing battle. She was having too much fun being a daily shit-disturber. Everyone who knew her always said it was like fighting with a cloud; you could never win.

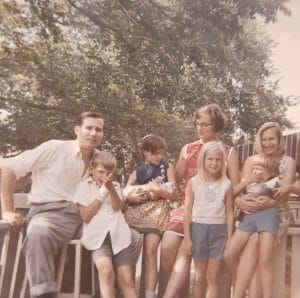

In an era when many American women stayed home, Helen worked, while her children, amongst the first of the latch-key generation, relished in the freedom this independence afforded. A curious and energetic bunch, they turned their neighborhood into a setting for modern-day Mark Twain adventures. It’s a wonder all survived into adulthood. Freedom was more than a concept to the Klingenbergs. They lived without reproach. Helen sunbathed topless on their deck and her husband Chrisoph often mowed the lawn in his boxers. They didn’t understand the Puritanical attitudes of their adopted homeland. Though not indifferent to the opinions some people had about Germans after the war, they kept a thick skin and, with a nonchalant shrug, they moved on.

Helen’s storied life took a tragic turn in the winter of 1977 when Christoph died of a brain tumor. Beyond love lost, it was an unmooring for the family. He had been the orderly one in the relationship, the captain of the ship, so to speak, the glue that held the family together. Grief-stricken, Helen desperately looked for a sign from the other side, eventually settled his affairs, put his paintings and poems and numismatic collections away, marked his grave with an abstract iron sculpture signifying the Last Supper by their friend Brother Mel, and forever kept him in her heart, never remarrying. At the age of 49, she set off on a new path, becoming the landlady of a quaint 16-flat apartment building and earning her real estate license, in addition to continuing to work as a part-time EEG technician in a neurologist’s office.

Her mother came to live with her for a period, enjoying time with the grandchildren she hadn’t seen in years. But, homesick for the small German town where she could walk everywhere, Mama returned home after a year or two. Eleven years into widowhood, Helen became a grandmother herself, and talents that had been shelved for decades came back to the forefront.

She knitted constantly — creating an abundance of blankets and sweaters and booties and hats that got handed down from grandchild to grandchild — seven in all. Even though her children and their families all lived close by, Grandma Helen was never the kind who longed to babysit and bake apple pie. Her husband had been the chef in the family. He prepared traditional German suppers with krispy kraut and sausages like blutwurst and teaworst, which could be found at a butcher shop near Bevo Mill in the Dutchtown neighborhood of St. Louis’ southside. Mealtime was accompanied by a glass of Cherry Heering for all, children included. Helen, on the other hand, was a notoriously bad cook. Her idea of a good meal was a box of cream puffs paired with Bailey’s Irish Cream. Her family claimed she could even burn water.

Although she worked most of her life, Helen’s real expertise was in knowing how to play by manufacturing luck-laced adventure. On their family trips to Florida, she swam in shark-infested waters. When they visited South Africa, she ate fried ants in Soweto. She enjoyed playing board games and dabbling in art, especially photography, which became a choice tool for annoying her camera-shy children and exploring the natural world. She took pictures of her kids, but also filled rolls of film with images of flowers, bugs, and sunsets, which she then developed in her bathtub. Always musically talented, she easily tapped out a tune on the piano or piped a song on the recorder, when she hadn’t touched an instrument in decades. Even in her 80s, despite gnarled arthritic fingers and osteoporotic hips, she had remarkable hand-eye coordination and spunk. On occasion, she could be found in the back yard with a lacrosse stick in hand, playing catch with her grandchildren.

Time waned, but family ties did not. For ten years before she moved into the nursing home, Helen was blessed to remain close to her children. She saw or talked to each one almost every day. When one of her sons and his family moved right next door, she saw it as an invitation to stop by for a cup of coffee unannounced at any hour, or to urgently call them over at midnight to smell the fragrant flower of her Cereus plant, which blooms only once a year for a single night.

During those later years, she relished time to reflect on books like Oliver Sacks, “The Man Who Mistook HIs Wife for a Hat” and other stories about neurological disorders or death and dying. She scrawled her thoughts into wiro-bound notebooks, which stacked up on her bedroom dresser. Her cat Tuffy and dog Sammie were her constant companions. When Helen encountered neighbors on walks, she would tell them Sammie was a coyote. It was impossible to tell if she was serious or joking. The conversation would soon turn as Helen pointed to a

cloud formation that looked like Colonel Sanders or picked up a fallen katydid whose iridescent wings reflected the orange and purple hues painted on the western sky as she turned it in her hand.

And so the story winds to a close. With her body curled in retreat, ready to leave her illustrious life, Helen opened one eye, then both, glanced up and back down, looking into the faces of family kneeling at her bedside. Years earlier Alzheimer’s had taken away her ability to write and speak, but with that wondrous gaze she reached out in the one way she still could and said goodbye.

Helen was known for saying, “I do it my way.” And that she did. Rest in peace, our dear Helen. The world will never be the same without you, and Heaven will be forever changed with you in its midst.

—–

Preceded in death by her loving husband, Hans Christoph Klingenberg; her Papa and Mama, Robert Vsevelod von Lerche and Benita Tamara (von Kraack) von Lerche; son, Gregory York Klingenberg; brother-in-law, Ernie (Victor) Klingenberg and his wife Sharon; sister-in-law, Juliane (Klingenberg) Dichter; cousin, Peter; and parents-in-law, Hans Ernst Victor Klingenberg and Eva (Siehl) Klingenberg.

Survived by her daughter, Eva Benita Matthews (Thomas Matthews and children Cameron, Thomas, and Michael); daughter, Iris Margaret Louise Risler (children Nicholas and Sasha); son Michael Meinhold; daughter-in-law, Jolene Rae (Thorburn) Klingenberg and her children, Nathan and Eva; sister, Nata (von Lerche) Dyke (Roger Dyke and children, Helen La grange, Christopher, and Erika Rodin); sister, Luba (von Lerche) Koch (Rainer Koch and children, Zeike and Anika and their families); niece Lili (Dichter) Anderson (Mark Anderson and son, Chase Cook); nephew, Hans Jurgen Dichter; nephews, Ron and Brian Klingenberg and families; and niece Shavon Klingenberg and family..

Helen’s life will be honored next year in a private gathering in Wiesbaden, Germany, where family will be visiting the graves of her parents and toasting with a bottle of Bailey’s Irish Cream.

In her memory, take pleasure in all of life’s little things. Helen would tell you there is so much to see. You just have to look.

Donations in Helen’s memory may be made to any animal rescue organization. Helen would be happy if you adopt a dog, or better yet, a pet rat or tarantula. Or, if you find mice in your house, catch them and set them free in the church yard. Helen did all those things.

We miss you everyday Mom! We love you!

Love ,

Evi, Iris, Jolene , Nathan, Eva &Tom